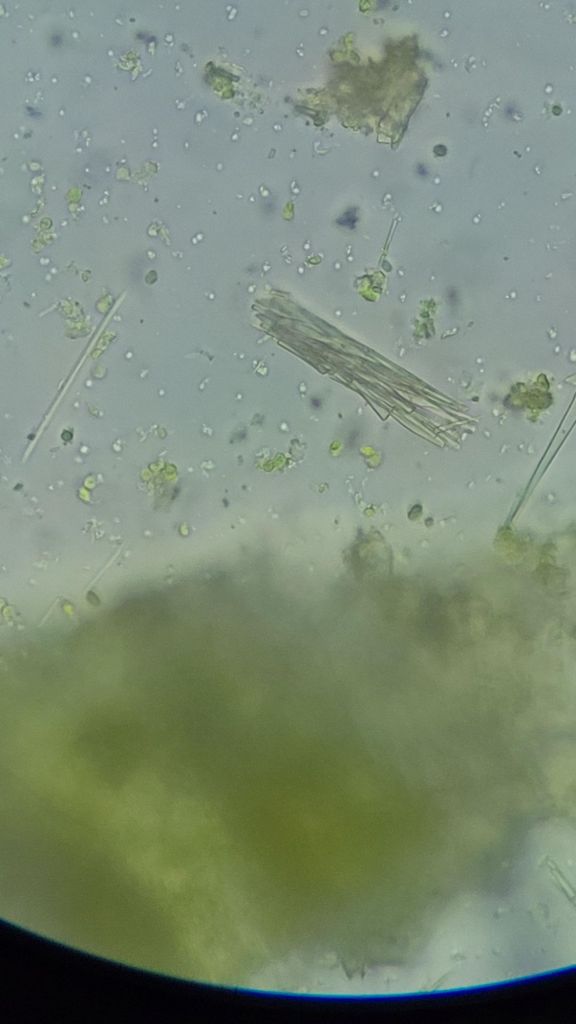

oxalic raphides in kanna sample

Traditional indigenous consumption of Sceletium Tortuosum included extensive preparation before consumption.

The plant was uprooted, crushed into a paste utilizing a mortar and pestle and then placed into a small bag to ferment. The fermentation process lasted about a week in which the bag was placed in the sun to heat up and speed up fermentation.

Once the fermentation was completed, the kanna was spread out and dried in the sun to prepare for consumption.

Why would the indigenous discoverers and botanical explorers choose to do this? The prevailing theories hold two explanations. Fermentation converts the alkaloids in the plant to the psychoactive components that the users of these plants are trying to experience. The second reason is all down to Raphides.

Raphides are microscopic needles of Oxalate crystals that are found in plant matter. Spinach, berries, and kanna, are all high in oxalates. Overconsumption of oxalates can result in irritation and kidney stones.

Referring to the picture at the top of the page, you can see the needle sharp oxalate raphides found in one of my Sceletium Tortuosum samples. Even though the raphides you can see in the sample are magnified 100x, it isn’t hard to imagine what damage those small spikes could do to your bodily systems if you frequently consumed large quantities of unfermented Kanna.

It is clearly evident that the indigenous pioneers that utilized this species of plant discovered this protocol for consumption and expended the time and energy to ferment Kanna for a reason and not frivolously.

Sources:

Rausch, Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. Rochester, VT, Park Street Press, 2005

Leave a comment