Jewelweed (impatiens capensis) is a common North American plant often found in moist, shaded environments like stream banks and woodland edges. It is easy to spot in the underbrush due to its burnt-orange flowers and its thick, translucent stalk.

Not only is the plant a gorgeous specimen, it has been used in the treatment of poison ivy and insect bites.

Identifying Jewelweed

Jewelweed usually grows between 2 and 5 feet tall and is easily identified by its translucent, succulent stems and pendulous flowers. The leaves are arranged alternatively, have a decent size (4in or so when mature), and are a toothed oval shape

There are two theories as to why it has the common name “jewelweed.” It either refers to the way water beads on its leaves and looks like jewels, or simply because the flowers resemble jewels.

If you touch the seed pods on a jewelweed plant, the seeds will explode out of the pod and disperse themselves. Thus referring to one of the common names: touch-me-not

Purported medicinal uses: poison ivy and insect stings

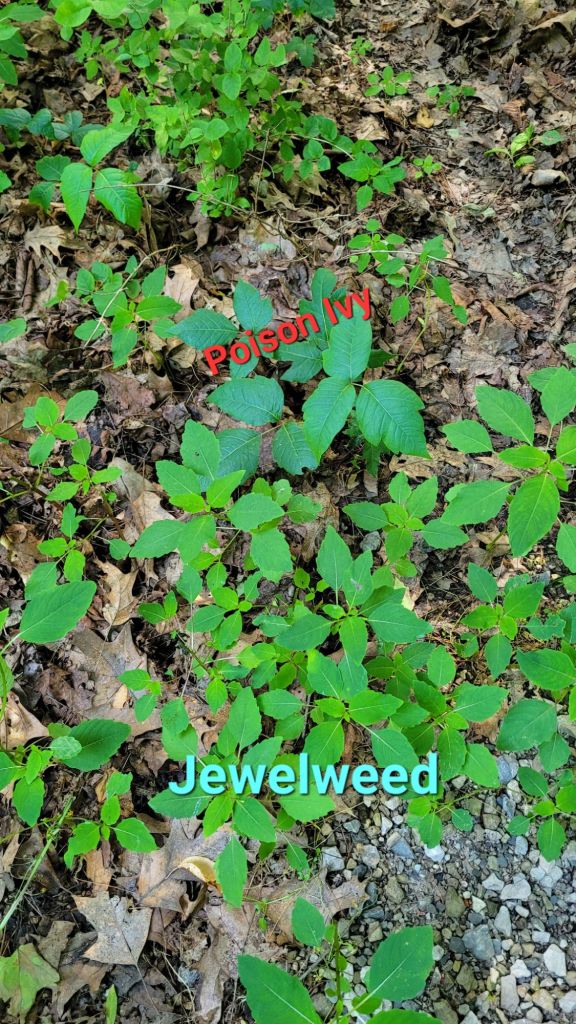

Thankfully, jewelweed can be used as a natural remedy for poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak, and poison sumac. Interestingly enough, Jewelweed is often found growing in proximity to the aforementioned plants. A herbal maxim I have recently heard is “the cure is often found near the poison”. Jewelweed definitely seems to follow this rule as I have recently seen jewelweed growing on top of poison ivy!

The sap found in the stems and leaves of jewelweed contains a chemical compound called lawsone, which reportedly has anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antihistamine properties. This compound is believed to neutralize urushiol, the oily allergen in poison ivy that causes rashes.

Traditionally, the plant is crushed and applied directly to the skin to relieve itching and reduce inflammation. I like to carefully cut a tube from the stalk, slit it open, and rub the slimy inner surface on the affected area. It feels just like a thin coating of Aloe Vera. This application is also useful for insect bites, which makes this plant a welcome sight to see in the wet woodlands it tends to grow in.

Jewelweed in its environment

I have found two interesting ecological uses for Jewelweed are as a pollinator food source and as a good erosion stabilizer. The plant’s vibrant flowers provide a nice target for hummingbirds, bumblebees, and butterflies. Since this plant seems to do well in a shaded understory, it provides good food sources for pollinators in areas where other flowers may be scarce. Also, since this plant tends to grow in wetter areas, the root systems can help in shoring up moist soils from eroding away.

Conclusion

Recently I have been tossing about an idea that I heard in a recent reading of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s fantastic book Braiding Sweetgrass. She posits that rather than usual view of nature as an uncaring force, that natural spaces love and care for the humans who understand and experience it. I think Jewelweed is a good indicator that her argument has some merits. It gives itself up readily in your time of need when you’ve brushed up against a poison ivy, or been stung by a flying denizen of the woods. You just have to speak the language of the forest to see the love mother nature has for you. And hopefully when you see Jewelweed from now on, you think about that concept.

Leave a comment